The Conscious Brain vs. the Unconscious Brain

“How can you think and hit at the same time?”

Yogi Berra Major League Catcher New York Yankees 1946 - 1963

“Man is a thinking reed but his great works are done when he is not calculating and thinking.”

Daisetz T. Suzuki Essays in Zen Buddhism Quoted in Zen in the Art of Archery 1953

“One of the most intriguing aspects of elite sports is that the athletes themselves have no idea how they do much of what they do, because it occurs beneath their conscious awareness."

David Epstein Author The Sports Gene Book Review on Amazon.com of The Performance Cortex by Zach Schonbrun

“The mind’s a great thing as long as you don’t have to use it.”

Tim McCarver Major League Catcher 1959 – 1980

“Understanding and being open to all things, Are you able to do nothing?”

Lao Tsu Chinese Philosopher Tao Te Ching 4th Century BC

“Therefore, do your allotted work regardless of results, for men attain the highest good by doing work without attachment to its results.”

Vyasa The Bhagavad Gita Hindu Epic Poem 100 BC

[If you have not read my previous article, You Can’t “Try” to Hit a Baseball, posted May 28, 2021, please do for it relates to this one as several references are made to that article, particularly to George Brett and his quest to hit .400 in 1980.]

A. Mike Schmidt's Dilemma. Being oblivious is usually not a good thing. However, being too aware is not necessarily a good thing either, especially when it comes to hitting. As for the answer to Yogi Berra’s question? Well, “you can’t think and hit at the same time.” (The 50 greatest Yogi Berra quotes) Sometimes, being smarter is not smart at all; it is actually dumber. And, that is in no way meant to throw shade on Yogi Berra, who, despite his reputation earned from stating his mind boggling Yogi-isms over the years, might have been one of the smartest players ever to play the game. As Yogi would have attested to, one can become so knowledgeable of how pitchers pitch hitters that they inhibit their ability to instinctively and spontaneously react at the moment they need to do so.

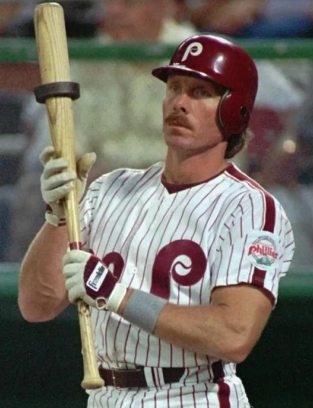

Philadelphia Phillies Hall of Fame third baseman, Mike Schmidt, understood all of that, the “dos and don’ts” involved in hitting a baseball well. Schmidt was more than capable of doing the “dos.” He just wasn’t always able to avoid the “don’ts.” This was particularly true during the 1983 season, Schmidt’s 12th with the Phillies. It was a year of highs and lows for him. Chief among the highs was his being voted by the Philadelphia fans as the greatest player in the organization’s history. The fan vote was part of the celebration of the team’s 100th anniversary of its founding. It was a great honor for Schmidt, as it would be for any player so chosen. He also went on to hit 40 home runs with 109 RBI that year, something most hitters would sign up for, then and now. But the lows – his inconsistent hitting - exasperated him. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that it was his exasperation that exasperated him. Schmidt only batted .255 on 136 hits. He struck out 148 times, the third highest total of his career, which broke down to one strikeout for every 3.6 at bats, a 27.7% strikeout rate. Put into the context of his career average - one strikeout in every 4.4 at bats, a 22.5% strikeout rate - and you can understand what he was going through and Schmidt unfortunately let the lows exasperate him. (Baseball-Reference.com)

On the eve of the 1983 National League playoffs, Schmidt confessed that his hitting struggles that year were attributed, in part, to his being “too self-aware” and his tendency to worry too much (I’m sure that the opposing pitchers would credit themselves for getting him out but that is not what this is all about. It’s about Schmidt’s mindset.). He said, “I know what my problem is. I’m too selfaware. I admit it. I might be too worried about everything.” (“Schmidt craves calm as Phillies move to playoffs,” The New York Times, October 3, 1983) What he meant was that he knew so much about the contest between a pitcher and a hitter that he thought too much and was, to his detriment, even worried about how the pitcher might pitch him. It is not easy to hit Major League pitching but it is much harder with such a mindset. He knew that his mindset interfered with his hitting. He found it difficult to trust himself. He was too conscious, aware. He tried to control the process by figuring out all of the angles, thinking about, and trying to predict, every pitch. One could say that he tried too hard. “I make myself crazy,” he said. Schmidt’s teammate with the Phillies from 1979 - 1983, Pete Rose, the all-time Major League leader in career hits with 4,256, said that, “Mike gets into trouble because he cares too much.” His manager with the Phillies in 1983, Paul Owens, was less kind. He said that Schmidt was just “insecure.” (“Schmidt craves calm as Phillies move to playoffs,” The New York Times, October 3, 1983)

Schmidt tried to self-correct. “I am going to try and keep my brain from thinking,” Schmidt promised himself. It sounded like a plan but he wasn’t always able to do that. He struggled with it as all athletes do at some point. It is a constant battle that the great ones eventually win. Schmidt apparently did. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1995. Yet, 1983 was difficult and Schmidt’s performance in the postseason was, like his regular season, marked by highs and lows. In the National League Championship Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers, Schmidt batted .467 only to struggle once again in the World Series, going 1 for 20 with only a single as the Phillies lost to the Baltimore Orioles.

Schmidt’s mindset of being “too self-aware” is not recommended. Yet, maybe there is another way to look at it, from the point of view of a Schmidt apologist. Maybe we can give Schmidt some credit, after all he is a Hall of Famer. Since Schmidt was inclined to analyze, he might have been ahead of his time. He might have been a better fit in today’s age of analytics. One can imagine Schmidt pouring over charts, graphs, and the most abstruse statistics that are an integral part of the game nowadays. It does make one wonder but we will never know. It is, therefore, safe to say that, during the era in which he played, Schmidt was guilty of being too aware, over-analyzing, and thinking too much. It was counter-productive and very frustrating for him and was, and is, for anyone with a similar mental approach to hitting.

One could also wonder if all of the data thrown at Major League hitters today - pitcher pitch sequences to ball spin rates to exit velocity to launch angles and more - will work for them either. The volumes of information, compiled and readily made available to today’s Major Leaguers, just may force thought processes on them that they might not otherwise engage in – being too aware, over-analyzing, and thinking too much. Worse, such information may cause them to think that they can control the uncontrollable - make themselves to hit a baseball, try. Heck, they could easily become new age George Bretts and Mike Schmidts, when both were at their worst. If you are prone to either the mindset of George Brett in 1980 or Mike Schmidt in 1983, you are really going to have a rough go of it, clog up the process – inhibit your reactions. It is all there in the library that is your cerebellum, which stores one’s learned movements, and the other parts of the brain that operate on an unconscious level. Remember that the pitcher has the ball. Only he and his catcher know what he is going to throw you, that is if you are not stealing signs and know what pitch is coming (see Part B, which follows). Hitting is all about reacting instinctively to a pitch as much as one can and trusting that one can react instinctively. Once a hitter learns how to hit, he has to let himself hit – “There is no try.” (THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK) Really, could Yoda be wrong? (See my last post of 5/28/21.)

I am not sure how transmittable Yoda’s arcane abstractions would be to today’s Major League ballplayers. Today’s great hitters might not even know who Yoda was. They may never even have seen any of the Star Wars movies, but they would intuitively understand the fictional Yoda’s message and probably have their own way of saying what would amount to the very same thing. However, they would definitely be able to relate to the very real cases of George Brett and Mike Schmidt and their struggles in the 1980s, for they likely experienced something like that at one time or another during their career. The admissions made by Brett and Schmidt could serve as a warning to any hitter in the age of analytics who thinks too much, then tries too hard. For now, it is safe to say that the jury, if one has been selected at all, is still out on the excess thinking involved in baseball’s information age. I’ll borrow another Yogi-ism: “If you ask me anything I don’t know, I’m not going to answer.” (The 50 greatest Yogi Berra quotes)

To read the article about Mike Schmidt, click the link below:

https://www.nytimes.com/1983/10/03/sports/schmidt-craves-calm-as-phillies-move-toplayoffs.html

B. Know the difference between the conscious and the unconscious part: Our brains function on a conscious and unconscious level. Neurologists and psychologists refer to it as dual processing. We will start simply. (Not coincidentally, that just so happens to be what Pete Rose always advised his teammate, Mike Schmidt, to do when he repeatedly told him to practice the K. I. S. S. method - Keep it simple, stupid!). Though I realize that this might not sound too simple to you, here goes. Consciousness is our awareness of our surroundings – physical, social, psychological, athletic, etc. That is what Schmidt was talking about when he said that he was “too self-aware” – all of that and then some. However, the way our brains operate on an unconscious level, a level outside of our conscious awareness, is what figures into how well, and how frequently well, a baseball player hits a ball. There are parts of the brain that deal in conscious processing (the more recently developed regions of the brain like the frontal cortex) and unconscious processing (the more primitive regions in the lower brain). Psychological science has demonstrated that the unconscious works faster than the conscious and even does so before the conscious part of the brain is aware of it (for more on this check out studies and experiments conducted by University of California, San Francisco neuroscientist Benjamin Libet, in which he demonstrated this). Essentially, for our purposes here, you did something. Let us say you hit a line drive double to the left center field gap, without realizing at the time what you did – what your various body parts did - to do that. That’s what Libet’s studies demonstrated, though he wasn’t dealing with baseball players, his studies are applicable. (Myers, 91)

If that is confusing, just go back to our default and refer to what Yogi Berra said about thinking and hitting at the same time. You can always rely on a Yogi-ism to make things clear, well, maybe. Yogi Berra understood it on a basic level, but he understood it in a way that might make most neuroscientists and psychologists envious. Berra kept it simple. Mike Schmidt, at times, struggled with that. When Berra or Schmidt were hitting well they were functioning on an unconscious level, not thinking about their mechanics or being aware that they were even in the batter’s box (unlike a weekend golfer wondering how to make every part of his body function to hit a golf ball well and worrying about what his fellow golfers might be thinking). The difference between operating on a conscious level as opposed to an unconscious one perplexed even great players like Berra and Schmidt, though Berra much less so. I am sure that they are not alone, for it probably would perplex most hitters. Therefore, the question is: How does a hitter get to that unconscious level to where he is operating at peak efficiency, free of thoughts that would impede his performance? Perhaps this example of a, then, 10-year- old champion cup stacker, Austin Naber, pictured below with Stanford neuroscientist, David Eagleman, can offer an explanation.

As he attempted to “peek into the mind of a champion,” Eagleman showed how, with hours and hours of practice - three or four hour a day practice sessions over a 34 month span - Austin Naber was able to cut the time it took to stack the ten cups pictured. When he first attempted to complete such a task, it took Naber two or two and a half minutes to do it. In time, it took Naber only five seconds! Eagleman stated that, “Our unconscious brain is capable of some truly remarkable feats.” However, he was not referring to his own “unconscious brain” in that statement and Eagleman’s attempts to do what Naber could do demonstrated that his neuroscientist’s brain was not as “remarkable” as Naber’s. Perplexed at the sight of this 10 year-old completing the task with such speed and efficiency, Eagleman had to ask Naber an obvious question: “So, when you do that [stacking the cups in just five seconds], are you thinking about what you are doing?” Naber replied, “Not really.” Eagleman asked, “You’re just letting your hands do the work?” Naber just nodded affirmatively. “Having to coordinate these complex actions so quickly,” Eagleman said, “it seems that his brain is burning a lot of extra energy.” The neuroscientist went on to say, “You might expect that his brain was working overtime.” To test his hypothesis, Eagleman rigged the both of them up to an electroencephalogram (EEG) to measure their brain activity while they were completing the task. An EEG enables a neuroscientist to record “electrical signals from the scalp to reveal clues about the activity going on inside the brain.” (THE BRAIN with Dr. David Eagleman, Episode 3) PBS television series The Brain with Dr. David Eagleman (Blink Films)

What Eagleman would discover was astonishing. As Eagleman and Naber dueled in the fine art and intricate science of cup stacking, the EEG recorded the “electrical world” within their brains. While Eagleman thought through the process, he deliberately, and, thus, very mechanically, stacked his cups. Naber sped through the task, freely and easily. Eagleman’s EEG lit up the screen, showing that Eagleman’s brain was hard at work with “a lot of energy being expended” (EEG shown at the left in the picture above) while Naber’s EEG was virtually dark (EEG shown on the right). Naber’s brain was “serene.” Click the link below to see Eagleman vs. Naber:

https://www.pbs.org/video/brain-david-eagleman-episode-3-clip-2/

Eagleman wondered how this could be. He knew the answer, even before he asked the question, though. The years of practice that Naber put in brought about “physical changes in his brain.” Skills like Naber’s cup stacking expertise are “hardwired into the structure of our brains.” Since Eagleman was a rookie at cup stacking, no such changes had time to occur in his brain. Thus, his attempts were methodical and slow, while Naber was so proficient, he could even stack his cups at his record speed blindfolded! Eagleman said that, “As we learn new skills, they change the structure of our brains. They move from software to become part of the hardware of the mind.” Naber had wired his brain into that of a champion cup stacker while Eagleman’s brain was only that of a neuroscientist learning to stack cups for the first time. (THE BRAIN with Dr. David Eagleman, Episode 3)

What is the takeaway? Our brains learn motor skills such as cup stacking, or hitting a baseball, through repetitive practice, lots of repetitive practice. Once we become proficient at such skills, we can do them unconsciously or automatically, eliminating the need to think our way through it. Hal McRae was a teammate of George Brett (pictured below) with the Kansas City Royals when Brett fell a little short of hitting .400 in 1980. McRae said, most likely affected by Brett’s masterful performance that year, that “The superstars are the ones who are unconscious. They’re in a trance.” (“By George, he almost did it,” Sports Illustrated, February 12, 1981)

C. You can't control the results, at least not the way you think. Another mental trap that one can fall into is thinking about the possible results of one’s efforts – whether they be positive or negative. Let’s say you are a hitter thinking too much about the score, outcome of the game, or your own statistics. Your brain would be working pretty hard with all of those things swirling around in there. You certainly would not be letting yourself go while in the batter’s box because you could not. You would be thinking too much. As a consequence, you would inhibit your reactions. You might likely try to control, manipulate, or guide your actions, as George Brett did in trying to hit .400 in 1980, or like David Eagleman trying to compete with a 10 year-old cup stacking champion. If you did that, as discussed before, you would NOT be able to react freely, at your peak level. You have to let yourself go, trusting your reactions! The score, outcome of the game, and the statistics are, and always will be, part of the game. Just accept that. You will not achieve a favorable outcome by being overly concerned with them. Sports Psychologist Harvey Dorfman gave this advice to hitters: “Set behavior goals, which you can control, rather than result goals, which you cannot.” (THE MENTAL KEYS TO HITTING, page 25)

While Brett was attempting to be the first to hit .400 since Ted Williams, it was disconcerting for Brett to come to the plate having seen his batting average in the newspapers and high on the scoreboard for all to see, especially himself. One at bat he is hitting .400. He makes an out and the next time the scoreboard reads .399. Another out and the next time it might say .398 and, so, it went the last month of that season. Brett said, “The thing I don’t want to do is put pressure on myself. But it's hard not to think about what I'm hitting. My batting average is in the papers every day and every time I go up to hit in Royals Stadium, it's up there out in center field on the scoreboard that's as high as a six-story building." (“George Brett Is Now a Happening,” The New York Times, August 18, 1980) After games, even if he was able to get it out of his mind, Brett was besieged by reporters asking him if he thought he was going to hit .400. This went on every day during the month of September and even before. He couldn’t escape thinking about the quest of hitting .400, no matter what he did. Talking about being too conscious or aware of the score, outcome, or results - could anyone contribute more to our understanding of this mental hazard than George Brett? (See my last post of 5/28/21 about George Brett if you haven’t already.)

Well, perhaps. Let us go back to ancient times (see the last quote at the beginning of this article). What could Vyasa, also known as Krishna Dvaipayana, the author of the epic Hindu poem, THE BHAGAVAD GITA, possibly understand around 100 BC about hitting a baseball and sports psychology? He did not know a single thing about baseball, for it would not come around for another 2,000 years. However, it sounds like he might have known more about sports psychology than we would likely think. What that ancient Hindu sage did understand, way back then, was that thinking about the results of one’s efforts would somehow interfere with executing the task-at-hand and prevent one from operating at peak efficiency, free from the constraints of his conscious brain. He would probably think that the thoughts that high school age players fall victim to, like wondering how a game’s at bats might affect their batting average or worrying about what a coach, parent, or teammate was thinking about their performance, would be things to be avoided. Did Vyasa understand that dwelling on the consequences of one’s effort interfered with how the brain operated? I doubt it (cognitive neuroscience was not around yet either) but it might be safe to say that this ancient Hindu sage was on to something about the possibilities and limitations of human actions and how being too concerned with the results of one’s actions adversely affected them. By the way, the book and the movie, THE LEGEND OF BAGGER VANCE, referred to in the article posted on May 28, was based on THE BHAGAVAD GITA. (Narasimhan, THE MAHABHARATA, pages 121-25)

D. “No mind.” There may have been help for George Brett and Mike Schmidt in the movie, THE LAST SAMURAI (2003). Unfortunately, they had retired from baseball by the time the movie came out. However, there are certain scenes in the movie that can help hitters with the psychological challenges the game of baseball can present, maybe not like the one Brett faced, but challenges nonetheless. Those scenes could help a hitter cope with an “awareness” issue like the one Schmidt had. Not for nothing, but I do wonder if Brett and/or Schmidt ever saw the movie and, if they did, they realized the lessons it could have taught them.

THE LAST SAMURAI told the story of a fictional U. S. Army Captain, Nathan Algren (played by Tom Cruise), a veteran of the American Civil War and the Indian Wars in the latter half of the 19th century. While the United States emerged from its Civil War and was continuing on its path of industrialization, Japan was attempting to cut ties with its past and undergo a process of technological advancement to rival other industrial nations at the time. While trying to make such a transformation, Japan was dealing with civil strife of its own. Following his retirement from the U. S. Army, Algren pursued an offer of employment from the Japanese government to travel to Japan to train its soldiers. The Japanese government was attempting to modernize its army and suppress a rebellion by Samurai warriors, who, seeking to maintain their traditional lifestyle and role in society, opposed the government’s policies. Algren’s work inevitably brought him into an armed conflict with the Samurai, who captured him during a battle.

At first, Algren’s captivity at the hands of the Samurai was extremely difficult and humbling for him, as he not only had to cope with his confinement but with himself and his own past as a soldier, something he was not proud of. His personal torment was eased somewhat by the support given to him by Nobutada (played by Shin Koyamada), the son of the Samurai leader, who assumed the role of helping Algren survive his incarceration while instructing him in the ways of the Samurai. As time went on, his treatment by the Samurai, and his interaction with them, came to profoundly affect Algren, gradually changing him as he came to reject his own way of life in America while adopting Samurai culture.

Algren’s education in the ways of the Samurai would include kendo, training with bamboo swords to learn the Samurai’s trademark swordsmanship. Kendo was not only meant to train the Samurai in swordsmanship, it was meant to keep the casualty rate down, for training with real swords would obviously be counter-productive. Though as Algren would learn, one could get hurt, physically and psychologically, training with Samurai warriors armed with bamboo swords. In the rainy scene pictured above, Algren was humiliated by the Samurai warrior, Ujio (played by Hiroyuki Sanada), who demonstrated just how good the Samurai were at kendo. They were pretty good with real swords too. After Algren was humiliated, yet again, while training with another Samurai warrior on another day, Nobutada offered words of advice to help Algren deal with his utter domination by the Samurai. Nobutada told Algren that he continued to suffer defeat because Algren was guilty of having “too many mind,” that his mind was cluttered – he was thinking too much. He was “too self-aware,” as Mike Schmidt would say,

Nobutada explained that “too many mind” involved three things – that Algren could not “mind the sword, mind the people watch, mind the enemy” and be successful in the training sessions with the Samurai. It wasn’t easy and Algren was certainly lucky that his training partners weren’t using real swords. Just saying.

Nobutada offered the solution to “too many mind.” He told Algren, “No mind!” In other words, he needed to clear his head of the clutter of unnecessary, self-defeating thoughts. One cannot, and therefore should not, focus on too many things, especially on extraneous situational factors that can enter one’s thoughts and interfere with one’s execution of a skill. Self-awareness was, or is, to be avoided when training with a wooden sword or hitting a baseball (George Brett reading the newspapers and looking at his batting average on the scoreboard and Mike Schmidt being “too self-aware”). Yogi Berra could easily have told Algren the same thing, and sound just as mysterious as Nobutada. Berra just chose other words. Nevertheless, Yogi knew. The fictional Algren eventually learned what “no mind” involved, and didn’t involve, as he went to fight with the Samurai against their government. Over time, he had become one of them. Click on the links below to watch the scenes from THE LAST SAMURAI referred to above:

Ujio humiliates Algren: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSB9VJcwQsc

Nobutada’s advice: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NbecIBvR3mE

Algren’s redemption – a draw: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7yP9MmzyTIg

What is the takeaway from all of these examples? It is quite simple. Keep it simple. Play the game. You must ignore the situational factors and not wonder about the possible results. You cannot allow such things to interfere with your performance. Avoid putting unnecessary pressure on yourself. Do not become like George Brett or Mike Schmidt. “Too many mind,” as Nobutada told Captain Algren in THE LAST SAMURAI, can only hinder your performance. Once you step into the batter’s box, “no mind” is the way to go. If you have the requisite ability and your hitting technique is fundamentally sound, honed by repetitive practice, the test of time and necessary trials will prove to you that you can get the job done. The results will take care of themselves – good results will practically become inevitable.

I realize that keeping it simple is actually a hard thing to do with coaches, parents, and teammates exerting pressure on you to perform (perhaps teammates to a lesser extent, I would say, since good teammates help each other deal with it). Thinking of all of those things - “mind” the crowd, your opponent, and your bat - would be to do so at your own peril. If you have read this article carefully, and understand its message, you should realize how the “no-mind” strategy applies and it is one you should put into practice.

“Um, I was just locked into the game and was going out there and doing my job.”

Craig Kimbrel

Fast forward to June 24, 2021, when four pitchers for the Chicago Cubs combined on a no-hitter against the 2020 World Series Champion Los Angeles Dodgers. Self- awareness; consciousness of the results; “too many mind?” Not on that day. Zach Davies was the starter for the Cubs, throwing six hitless innings. Ryan Tepera and Andrew Chafin pitched the 7th and 8th innings respectively. Craig Kimbrel closed it out. (Tepera and Kimbrel were traded to the Chicago White Sox and Chafin to the Oakland Athletics at trade deadline at the end of July).

Kimbrel, in his post-game interview, practically taught a sports psychology seminar on awareness, or lack of it. His reaction said a lot about being surprised too. (Refer to my previous posted article from May 28, “You Can’t ‘Try’ to Hit a Baseball” about Japanese archery master Kenzo Awa’s concept of surprise.) “I’m not going to lie,” Kimbrel assured his interviewer. “I had no idea, um, until the last out and everybody came running out. Um, I was just locked into the game and was going out there, doing my job. …I was like, man, something just happened. And, um, Tepera came out. He said, ‘You don’t even know what happened, do ya?’ I was like, I have no idea.” (“Kimbrel on combined no-hitter,” mlb.com/video/Kimbrel-on-combined-no-hitter).

“I had no idea. I was like, what did I do?

Corbin Burnes

On August 11, 2021, Milwaukee Brewers pitcher Corbin Burnes tied a Major League Baseball record by striking out 10 consecutive batters in a game against the Chicago Cubs. Maybe he saw Craig Kimbrel’s interview on June 24 since he reiterated what Kimbrel said, for he, too, confessed to being unaware of what he was accomplishing, that is, while he was accomplishing it. Burnes even repeated some of Kimbrel’s words! “I had no idea,” Burnes said after the game. “I was like, what did I do? Why are we throwing the ball out of the game? I had no clue.” It is interesting to note that when Burnes became aware of tying the record, the next batter hit a single on Burnes’ first pitch to him. Was the spell broken when Burnes became aware of his streak? Did that awareness cause him to fall out of the “zone” he was in? That would be my guess. Burnes did get it together and went on to pitch eight innings that day, striking out 15. Nevertheless, one would wonder if he could have broken the record if not for what his teammates did after he recorded 10 straight strikeouts. They made him aware or conscious of what he had done. They made him leave the “zone” he was in. (“Milwaukee Brewers’ Corbin Burnes ties record with 10 straight strikeouts,” ESPN.com).

By now, you should be able to guess what I am going to say. Well, maybe I will let someone else say it and defer to the author of The Sports Gene, David Epstein, who I quoted at the beginning of this article and will repeat what he said here. In writing a book review on The Performance Cortex by Zach Schonbrun for Amazon.com, Epstein said, “One of the most intriguing aspects of elite sports is that the athletes themselves have no idea how they do much of what they do, because it occurs beneath their conscious awareness." What Craig Kimbrel and Corbin Burnes had to say certainly could have been part of David Epstein’s review. It was not. Epstein wrote the review well before their accomplishments. However, it was better than that. They were trying to describe something they had done, something they were not even aware of when they were doing it. Kimbrel and Burnes had “no idea” that they were doing what they were doing. If asked, Epstein would likely say that their post-game statements were exactly what he was saying in that review that he wrote. Those mentioned in this article, whether they be real or fictional, would likely concur with Epstein, though the real one have not been asked and the fictional ones could not be.

What is the take-away? I will go back to my opening statement about hitting a baseball. Being oblivious is usually not a good thing. However, being too aware is not necessarily a good thing either…. Well, it applies to pitching too. As Craig Kimbrel and Corbin Burnes would attest.

References

Anderson, D. (1980, August). George Brett is now a happening. New York Times.

BaseballReference.com. (2000, April 18). Mike Schmidt statistics

https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/s/schmimi01.shtml

DiCosmo, A, (2021, September 13). Lindor has last word after benches clear. MLB.com.

https://www.mlb.com/news/yankees-mets-benches-clear-citi-field

Dorfman, H. (2017). The mental keys to hitting. Lyons Press.

Eagleman, D. (2017). The brain: the story of you. Pantheon Books.

Eagleman, D. (Writer) & Barden, G. Clifton, D. Gale, C. Gibbon, J. W. Jones, J. Stacey, N.

Trackman, T. (Directors). (2015). Who’s in control? [TV series episode]. Beamish, J. (Producers) Kershaw, J. The brain with David Eagleman. PBS.

Eberts, J. Nozik, M. Redford, R. (Producers) & Redford, R, (Director). (2000). The legend of Bagger

Vance [Motion picture]. DreamWorks Pictures.

Herrigel, E. (1999). Zen in the art of archery. Vintage Books.

Herskovitz, M. Zwick, E. Cruise, T. Wagner, P.Kroopf, S. Engelman, T. (Producers) & Zwick, E.

(Director). (2003). The last samurai [Motion Picture]. Warner Brothers.

Johnson, M. (Producer) & Levinson, B. (Director). (1984). The natural [Motion picture]. Tri-Star Pictures.

Jomboy Media. (2021, September 13). The Mets got mad at the Yankees for whistling, a breakdown.

Joyce, G. (2021, September ). Benches clear in Yankees-Mets game over alleged whistling. New York Post

Kurtz, G. (Producer) & Kershner, I. (Director). (1980). The empire strikes back [Motion picture].

Lucasfilm Ltd.

MLB.com. (2021, June 24). Kimbrel on combined no-hitter. MLB FILMROOM.

https://www.mlb.com/video/kimbrel-on-combined-no-hitter

Myers, T. A. (2011). Myers’ psychology for ap*. First Edition. Worth Publishers.

Narasimhan, C. V. (1965). The Mahabharata. Columbia University Press.

Shainberg, L. (1989, April). Finding the zone. The New York Times Magazine, p.35.

Sherman, J. (2021, August 30). Steve Cohen: Mets players hit ‘the third rail’ with thumbs-down at fans.

New York Post. https://nypost.com/2021/08/30/steve-cohen-mets-hit-the-third-rail-with-thumbs-down-at-fans/

Schoenfield, D. (2021, August 18). Milwaukee Brewers’ Corbin Burnes ties record with 10 straight

strikeouts. ESPN.com.

Scott, N. (2019, March 28). The 50 greatest Yogi Berra quotes. USA Today.com

https://ftw.usatoday.com/2019/03/the-50-greatest-yogi-berra-quotes

Thosar, D. (2021, August 24). Mets players are celebrating by giving their fans a thumbs down. New York

Tsu, L. English, J. Feng, G-F (Translators). (1972). Tao te ching. Vintage Books.

Wolff, C. (1983, October). Schmidt craves calm as Phillies move to playoffs. New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/1983/10/03/sports/schmidt-craves-calm-as-phillies-move-to-playoffs.html

Wulf, S. (1981, February). By George, he almost did it. Sports Illustrated.